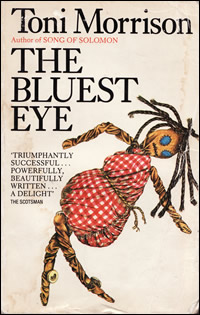

Is beauty really only skin deep if the world we occupy behaves as if it is? Toni Morrison explores the reality for an African family living in America at a time when segregation, ‘white’ supremacy ideology and its supporting overt racist apartheid system was embraced and proudly acknowledged ‘as American as apple pie’.

I’ve often heard it said that reading Toni Morrison is quite difficult. For those discussing her style I have a little sympathy, indeed there is a case to discuss. However having now read her first novel The Bluest Eye I think what some people are really trying to say is that her works can make for difficult reading - if you are a man. I have to state first of all that I disagree with this notion. Whilst it can be argued that almost all the male characters in this particular story were pathetic abusive creatures driven by carnal desires, the central narrative driving this tragic tale was one of unbridled love.

Morrison’s writing style in The Bluest Eye is heavily character driven. The events and incidents that join the cast are almost incidental to her developing the flesh of her actors’ inner being. Almost every chapter is written like poetry, each sentence and word reflective of prose designed to soothe the soul during even the most disturbing of scenes.

Although the main protagonist could be seen as the eleven year old Pecula, an innocent African girl desperate to posses the blue eyes mentioned in the title and and therefore become ‘beautiful’, the truth of the matter is that her life is merely the convenient lens enabling us to examine the backdrop of her mother Pauline and father Cholly. Morrison exposes us to the horrific circumstances leading this family to a path of spiritual impoverishment and physical self-loathing.

Despite addressing uncomfortable topics such as incest and child abuse Morisson makes a brave attempt to delve into the motivation behind those responsible for abhorrent actions. In so doing, she uses history as a means to provide context but never justify the actions of men committing crimes. In seeking to help us understand her male characters Morrison managed to ensure she never reduced them to simple minded ‘bad’ people thereby abdicating their personal responsibility and perhaps more important - their capability to stop themselves abusing their authority. Women were also drawn with multiple attributes depicting the virtuous to the most amoral. It is this balanced approach to the tale that helps make the book so engaging. African women are not only abused by men, but also by european women as well as themselves both physically and spiritually.

Indeed if there is any weakness throughout it is that the story is so sad, so tragic. As a reader the majestic beauty of her writing almost compels you to seek and be hopeful for a source of emancipation, but the words of redemption teasingly never truly come. As a result some could criticise the story as purposeless, existing without living, talking without speaking. This would be unfair.

In defence it is tempting to detail the intricate web she weaves between mother, father, siblings, friends and community. The manner in which the backdrop of racism is ever present but never dominant, the enormity of the rare and singular explicit reference to African identity, the colloquial use of language adding cultural authenticity making the infrequent use of the n word seem unnecessary and even clumsy. The chapter titles themselves are exquisitely formed as parts of an opening text that parodies the world made real by her holistic depiction of despair, hope and lost potential.

So how to conclude? Well it is in-between the words written to the Creator by the irredeemable spiritualist character named Micah Elihue Whitcomb and that of the inner dialogue with Pecula that the story delivers its most potent message. It is here that Morrison unleashes a quiet fury at those who would and have denied and defiled the potential good of human nature and the consequences of Africans who would seek to imitate the way of these demons and devils.

Is it illogical sanity to accept this behaviour as normality or wise insanity to seek refuge in the beauty of perceived abnormality?

Reading this book it is difficult not to concede a Truth that sadly remains the same today as in 1970 when this superb story was first published forty years earlier. That is, that it was never Pecula who was ugly but the world she inhabited.

External Links

Toni Morrison Society

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

Morrison’s writing style in The Bluest Eye is heavily character driven. The events and incidents that join the cast are almost incidental to her developing the flesh of her actors’ inner being. Almost every chapter is written like poetry, each sentence and word reflective of prose designed to soothe the soul during even the most disturbing of scenes.

Although the main protagonist could be seen as the eleven year old Pecula, an innocent African girl desperate to posses the blue eyes mentioned in the title and and therefore become ‘beautiful’, the truth of the matter is that her life is merely the convenient lens enabling us to examine the backdrop of her mother Pauline and father Cholly. Morrison exposes us to the horrific circumstances leading this family to a path of spiritual impoverishment and physical self-loathing.

Despite addressing uncomfortable topics such as incest and child abuse Morisson makes a brave attempt to delve into the motivation behind those responsible for abhorrent actions. In so doing, she uses history as a means to provide context but never justify the actions of men committing crimes. In seeking to help us understand her male characters Morrison managed to ensure she never reduced them to simple minded ‘bad’ people thereby abdicating their personal responsibility and perhaps more important - their capability to stop themselves abusing their authority. Women were also drawn with multiple attributes depicting the virtuous to the most amoral. It is this balanced approach to the tale that helps make the book so engaging. African women are not only abused by men, but also by european women as well as themselves both physically and spiritually.

Indeed if there is any weakness throughout it is that the story is so sad, so tragic. As a reader the majestic beauty of her writing almost compels you to seek and be hopeful for a source of emancipation, but the words of redemption teasingly never truly come. As a result some could criticise the story as purposeless, existing without living, talking without speaking. This would be unfair.

In defence it is tempting to detail the intricate web she weaves between mother, father, siblings, friends and community. The manner in which the backdrop of racism is ever present but never dominant, the enormity of the rare and singular explicit reference to African identity, the colloquial use of language adding cultural authenticity making the infrequent use of the n word seem unnecessary and even clumsy. The chapter titles themselves are exquisitely formed as parts of an opening text that parodies the world made real by her holistic depiction of despair, hope and lost potential.

So how to conclude? Well it is in-between the words written to the Creator by the irredeemable spiritualist character named Micah Elihue Whitcomb and that of the inner dialogue with Pecula that the story delivers its most potent message. It is here that Morrison unleashes a quiet fury at those who would and have denied and defiled the potential good of human nature and the consequences of Africans who would seek to imitate the way of these demons and devils.

Is it illogical sanity to accept this behaviour as normality or wise insanity to seek refuge in the beauty of perceived abnormality?

Reading this book it is difficult not to concede a Truth that sadly remains the same today as in 1970 when this superb story was first published forty years earlier. That is, that it was never Pecula who was ugly but the world she inhabited.

External Links

Toni Morrison Society

Ligali is not responsible for the content of third party sites

Get involved and help change our world